HELEN FRANKENTHALER AT SKOWHEGAN

September 30, 2017

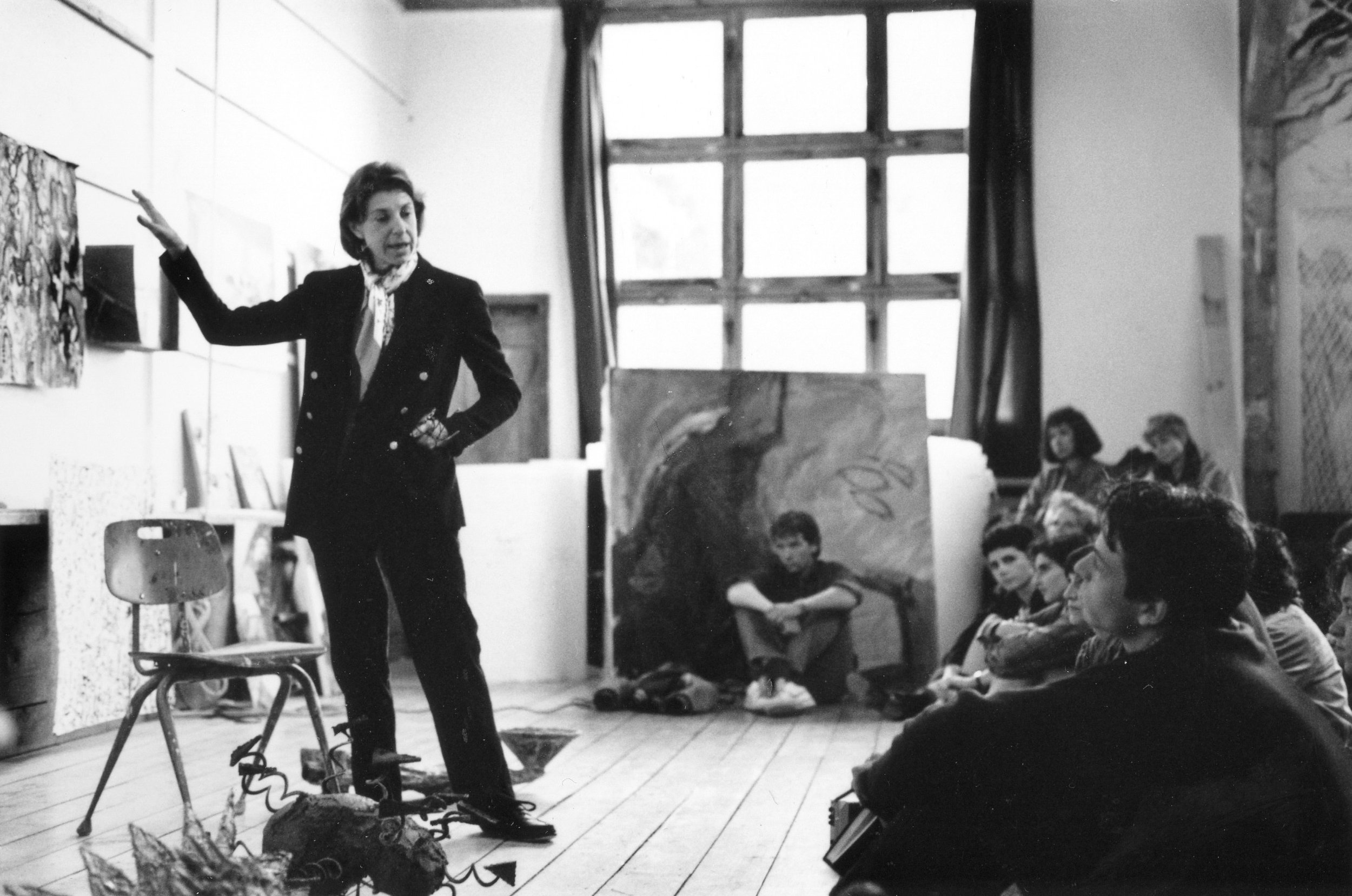

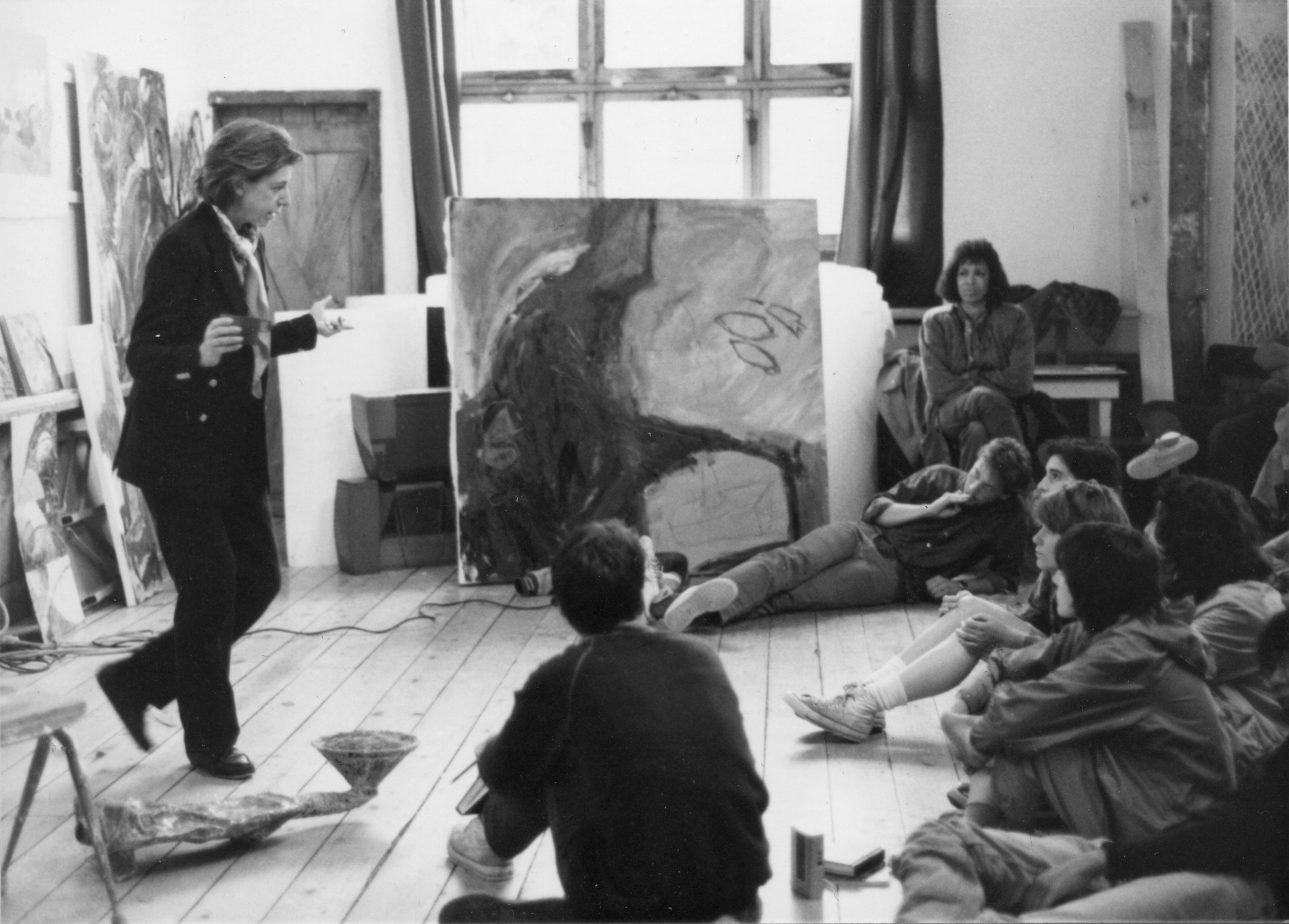

Helen Frankenthaler came to Skowhegan during the summer of 1986 as a visiting faculty artist. In addition to conducting studio visits with participants, she gave a lecture on campus in the Old Dominion Fresco Barn. This talk, excerpts of which can be explored below, is preserved in Skowhegan’s Lecture Archive, a trove of lectures by faculty and other artists who spoke at Skowhegan dating back to 1952.

On October 5th, 2017, Skowhegan announced that it has received a $250,000 gift from the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation. The funds will provide for a new studio building which will be named in Frankenthaler’s honor, acknowledging her deep commitment to studio practice, and will accommodate discrete workspaces for three visual artists. When complete, the Frankenthaler Studio will be the 15th studio building on Skowhegan’s 350-acre campus, joining those named for other artists who taught at Skowhegan, including founder Willard “Bill” Cummings and Jacob Lawrence.

Read the full release to learn more about the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation's gift.

Helen Frankenthaler Lecture

Old Dominion Fresco Barn, Maine Campus

1986

Helen Frankenthaler: “Okay. New work. I wrote this in the middle of the night, in quite a panic, one night, feeling I'd been looking at all this new work and very alone for about a year and a half. I had this body of work, and I felt, I don't know if it means anything. Then I felt, well, what about my past, and other artists' pasts, and everything else. So for a few nights, on and off, I would just make some notes about new work. These are some of them, in no particular order.

New work: People often go up to an artist and say, ‘Are you doing any new work?’ Or, ‘I hear you have a body of new work.’ The artist is usually taken aback by such a confrontation. Recently, after many such inquiries, I literally sat down and gave some thought to what, really, new work means.

What does it mean when an artist presents new work? Recent work? Or fresh work, the beginning of a new phase, or spirit? A new direction or the hint of one?

Does the artist fully realize what he's accomplished, what he's doing, what he's up to?

How does it look different?

How has it developed? Does it make a new statement? Hopefully, does it enlarge one's truth? Are we shocked or puzzled by it in a fresh way? And are we shocked in a way that goes beyond initial shock? That is, beyond entertainment, but, instead, a shock that eases us into seeing and enjoying, and growing with beauty?

Is the new work a minor departure or a significant breakthrough? A new way ‘to see’? A magic that combines a repetition of the past within a new vision, within the context of the artist's whole aesthetic gestalt — the eye, the mind, the wrist, the leap of heart that physically places the mark.

When an artist is developing a departure within his aesthetic, there is an initial shock, or surprise, of a first picture. For myself, I can think of how I felt first looking at Mountains and Sea, 1952; or Sesame, 1970; Roulette, 1978; or the blue one [Out of the Blue], 1985; the one I said I'd painted just about a year ago, the first of a series.

Then a body of work usually follows those pivotal pictures and grows within the context of that initial shock. Eventually that core of work enhances and restates and explains, that first surprise picture. Nothing comes out of the blue. Mountains and Sea, for example, was followed by many years of soaked, stained work, placed on unsized, unprimed cotton duck. Which really isn't true. It wasn't many years. It was maybe one of the first, but many years of pictures that led up to it. Also, what I forgot to write was that I'd spent a summer of doing nothing but landscapes in Nova Scotia that year and suddenly did Mountains and Sea after many, many small landscapes. I'd already been an abstract painter, but I spent the summer just doing what I call ‘verbatim landscapes’ — the tree that looked just like the tree.

Small’s Paradise, 1964, and Buddha’s Court, 1964, reinforce the format of the square and also began what later, much later, became tinted ground, tinted ground rather than merely leaving the duck the color it is, naturally.

The blue one painted in June 1985 spawned many pictures. I would guess about one third of those I destroyed in the process, right or wrong, out of doubt.

Sesame

Helen Frankenthaler

Sesame, 1970

Acrylic on canvas

106 x 82 1/2 inches (269.2 x 209.6 cm)

Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, N.Y. Photograph by Tim Pyle.

All Artworks © 2017 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The following new body of work, what you saw, hopefully continues to resolve that first surprise picture, which seemed awkward, inevitable, and at the same time to have the sense of rightness, the certainty of the mark. A new painting has the authority of saying, in effect, ‘I had to be made!’ It has the sudden look to it, and to the artist himself. But when we look at that one, seemingly simple gesture of the new work, of a new picture, all the effort, search, failure, confusion, and often depression that preceded it seems to show not at all.

That is one side of the coin — it doesn't show at all. [From the other,] you know that, in order to do this, the artist must have felt certain ways — and I think the older you get the more you appreciate that — even if it's the most sunlit, primary-colored, left-handed dream of a picture. Well, that's one reason you can tell the difference, in a flash, between a kid's picture and a grownup's. Very often people say to you, ‘Who made this?’ And I'll say, ‘A very free, wonderful four-year-old who has no guilt yet, just an angel, but a kid.’ And they'll say, ‘Gee, I would have sworn it was a Matisse.’ I feel [like saying], You dope! [Audience laughter] It’s another trip.

Where was I?

It's only a lucky moment, all things combined, that the artist and the picture itself, together, say ‘give’.

And then I just have some other notes, such as space and light: The shapes and forms that one first puts down are the need and excuses for putting down the right colors, exactly where they belong, in a given space. There should be a constant dialogue between color and line, and all within the perfect scale and light. And you have an intuitive sense of placing within that scale.

And that's it on new work. So. Speak. Or don't.”