FRESCO: THE GOLDEN TIME

An interview with Skowhegan Fresco Instructor Sean Glover (A '03).

February 28, 2020

Fresco has been part of Skowhegan since its founding in 1946. Campus remains one of the few places in the United States where this technique is still taught and practiced by contemporary artists. In this interview, Fresco Instructor Sean Glover (A '03) gives a history of the medium at Skowhegan and a provides a glimpse into the practice on campus today.

What is the history of fresco at Skowhegan?

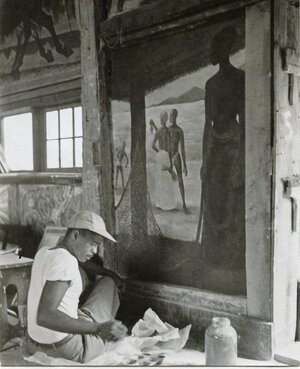

Skowhegan was founded by four artists (Bill Cummings, Henry Varnum Poor, Sidney Simon and Charles Cutler) who came together after World War II, at the end of an era in which social realism and mural painting were very popular. They wanted to create a space not only for artists to go and practice and reflect and learn from one and other, but also pick up practical skills. Because fresco was still a part of the broader artistic conversation of that moment, people could learn fresco at the school and use that skill to get commissions for major jobs. Henry Varnum Poor had worked on frescoes with Diego Rivera, and we still use some of his techniques at Skowhegan today.

Since then, the culture has shifted. There are different materials, different approaches to making art— post-studio practice, conceptualism, time-based media like video—all of these things have come into the fold and fresco has moved to the periphery. So when I talk about fresco at Skowhegan, I try to emphasize that by participating in it, you're contributing to the history of the school and coming into contact with its foundation.

Fresco is a unique process that has emerged in many different cultures, often ones that have had little or no contact with each other. When you work with fresco, you’re interacting with something really ancient, but also something very immediate. You're touching base with different sites and architectures, different cultures, and of course a broad range of subject matters. I describe it as a kind of "meta-process," or "meta-material." It's loaded just by participating in it. Fresco is unique in that way.

Sean Glover (A ‘03) and participants preparing pigments for fresco, 2015.

What is Fresco?

Fresco is the process of painting into wet plaster. The plaster is made of calcium hydroxide, or lime. When you paint into the plaster, you're participating in what is called a "fresco cycle," where the material begins as a rock, is processed and aged, and then is applied to a wall. When the plaster is applied to the wall, it wants to return to its initial rock state, so your time painting is actually the very end of that cycle. As the plaster dries, a calcium carbonate crystal forms over the paint and retains the pigment, which is what sets fresco apart from other mural painting: the painting is physically a part of the wall, physically set into the architecture. It's not laid on top; it's fused with it.

Working with fresco requires negotiation with the surface. A newly formed, newly wet wall—what I call a “young” wall—does not completely absorb paint, forcing you to temper yourself and slow down. Then as the wall begins to dry, it becomes important to approach the painting holistically, hydrating the wall by adding water to the entirety of the surface as you work. This process extends the painting and forms stronger crystals.

Sean Glover (A ‘03) and participants preparing pigments for fresco, 2015.

The Fresco Shop is an interesting dovetail to the time-based work done in the Media Lab, where you can go back and edit your work. You can go back in time in a certain way. In fresco, it's not as easy: if you try to go back and lift up or erase, you compromise the surface in a way that actually dampens the color. So there's this kind of balance you have to strike with the surface.

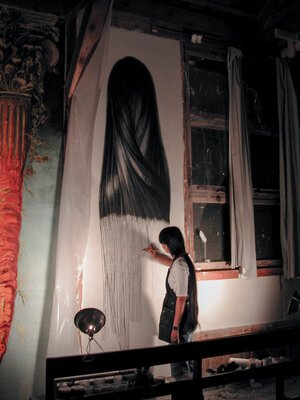

At the end of the fresco cycle, a shift occurs where you are able to start employing the traditional conventions of blending and moving paint on the surface, techniques that you initially have to put aside. This stage is what the Italians call the “tempo d’oro” or the golden time.

There is the romantic idea of the artist working alone in their studio and having this kind of intimacy with the image. Tempo d’oro is a rare moment where the romantic image of the artist and the chemical reality actually coincide. By spending your time working with the wall, you actually earn that moment. It's a transformation that you bear witness to which can only happen if you're working with the wall constantly, with sensitivity to the character of that material.

What impact does fresco have on the participants?

I trust the participants to make their own image. I don’t give them input on the image during the workshops, but I do hold them accountable to the wall. In addition to participating in the history, and having that moment where it’s just the artist and the wall, I want them to understand that the labor put into the surface is inherited by next year’s class. Participants work with the wall for roughly three hours. This can be a revelatory experience where they start to confront labor and really begin to understand the intensity of having to refine themselves and respect the craft. Often people remark that this experience really shapes them and makes an impression on their practice.

In the painting process, the inability to edit as you go has sparked conversations with participants about accepting mistakes and then actually integrating them into the work, as well as the concept of “perfection.” Putting aside some of the preconceptions of what painting is lets new gestures—new ways of working and thinking about the wall—emerge. This is generally how things shift: by offering flexibility, you end up with some surprises. I find it really exciting to hear different approaches of working with the material. As I've taught over the years, the conversations have shifted toward thinking about working with something other than ourselves, and exploring how that translates to more than just painting.

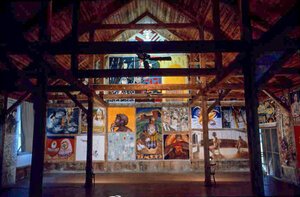

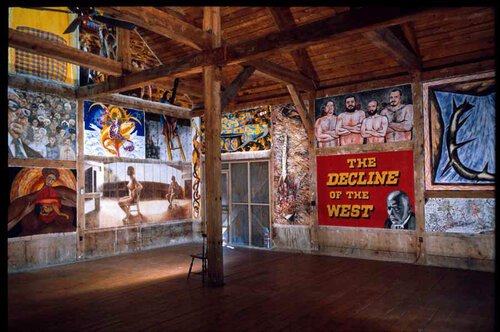

Fresco Grotto, a collaborative fresco created by the participants of 2017.

During the summer of 2017, artists at Skowhegan created a 25 ft. x 15 ft. Fresco Grotto, linking the history of meditative sites of refuge to the experience at Skowhegan as space of creative practice and reflection.

How did this project come into being?

The Fresco Grotto began with resident faculty artist Angela Dufrense saying, "Why don't we try doing a fresco that is off-site, away from the barn?” She started with this theme of “the grotto.” With Angela Dufresne's aesthetic, it aligned with not only the way she paints, but also the way she thinks of the world, or some of her interests in the world. People became really energized and excited about that possibility, and the class’s openness and willingness to contribute is really where it began.

We took some risks with the Fresco Grotto, because we had limitations regarding the installation—we couldn't attach a permanent fresco inside the building without having to dismantle it or figure out a tricky way to attach to the wall, so it needed to be temporary. We found an underutilized space and created this system of splicing together foam, which, with respect to the broad history of fresco, is a brand new approach. The participants organized themselves to build this in phases over the course of the summer.

Fresco Master Renato Giangualano at the Fresco Intensive, 2017.

All together, I believe there were 20 to 25 people involved in the creation of the Fresco Grotto. Not everyone was interested in painting and instead simply wanted to participate, contribute, and help others realize it. They wanted to see what they could do, and how they could collaborate to make a unique presentation of fresco on campus. There was a spirit of curiosity and a willingness to do some hard work. They pulled it together and made it happen. It was really remarkable and I couldn't be more pleased with it.

After the 2017 session ended, a group of alumni with advanced fresco expertise participated in a 10-day fresco intensive on campus with Fresco Master Renato Giangualano who traveled from Italy to lead the workshop. The group took a deep dive into materials and techniques that expanded their knowledge of the medium, passing the tradition of this material from one generation to the next, and ensuring that Skowhegan will continue to hold knowledge of this increasingly rare practice.

A second workshop was held in August 2018. This session also concerned the conservation of an outdoor fresco from 1955 by Annie Poor commemorating Skowhegan’s Founding Families and located at Sap House, next to Red Farm. Preserving this part of Skowhegan’s history and recognizing Poor’s critical role in the first three decades of the school are meaningful in setting the stage for Skowhegan’s future.

What are the next steps of this restoration?

The wall on which Annie Poor’s fresco is mounted is a little unstable, in part because it is wicking up moisture and salt through the cement. Currently, we're in the process of creating alternate vents so that the wall no longer draws in salts from the ground, which is damaging to the fresco. This process began with Bill Holmes, Grounds and Maintenance Manager, and his crew excavating underneath Sap House and putting mechanisms in place to ensure that not too much water comes up. We're doing the final parts of that process, slowly going in and reinforcing the back of the wall and coating it with materials that allow it to breathe, but not draw in water.

The other part is the restoration of the face of the fresco. Fresco Master Renato Giangualano, who led the workshop, helped us devise the restoration plan. He is lending his expertise for all aspects of the restoration, but with regard to working on the face of the fresco itself, he will actually come in and have his hands on it.

Each participant in the Fresco Intensive came from a different background. Was Renato Giangualano surprised by the diversity of experience?

He was excited by it, while also bringing his own traditional knowledge and perspective. When people would share their own methods, he might say, "You can do it that way, but here’s the way it is traditionally done." He's very well versed and intimate with the process, but he understands that he's just one voice in the tradition. It’s more important to him that people are invested in learning and exploring.

In my case, I am a sculptor. My first encounter with fresco was when I signed up to be a fresco monitor during my summer as a participant just to hang out with Daniel Bozhkov, A '90, F '11, and longtime fresco instructor. I am not really trained as a painter, but that has never waivered Renato’s interest in sharing his knowledge with me. I'm really grateful for that, and that's something I know Oscar [Rene Cornejo A ’14, Program Coordinator and Fresco Assistant] and I try to provide to participants as well. We want to engender a kind of openness and push things toward that spirit of curiosity.

What Renato appreciates and what he loves about Skowhegan is that investment in exploration. People here are very committed to searching through material and art with real sincerity. They let down their guard and they can show that sincerity in a way that’s not always possible outside of this place. And it’s that tendency toward openness which begins here at Skowhegan that can often resonate beyond the summer.