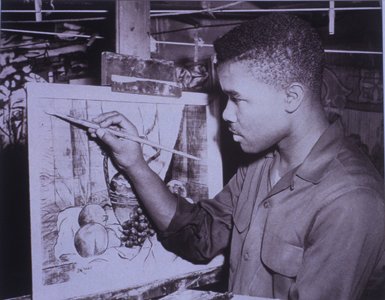

DAVID C. DRISKELL

(June 7, 1931–April 1, 2020)

Alum: 1953

Faculty: 1976, 1978, 1991, 2004

Board of Governors: 1975–1989

Board of Trustees: 1989–2002

Advisory Committee: 2003–2020

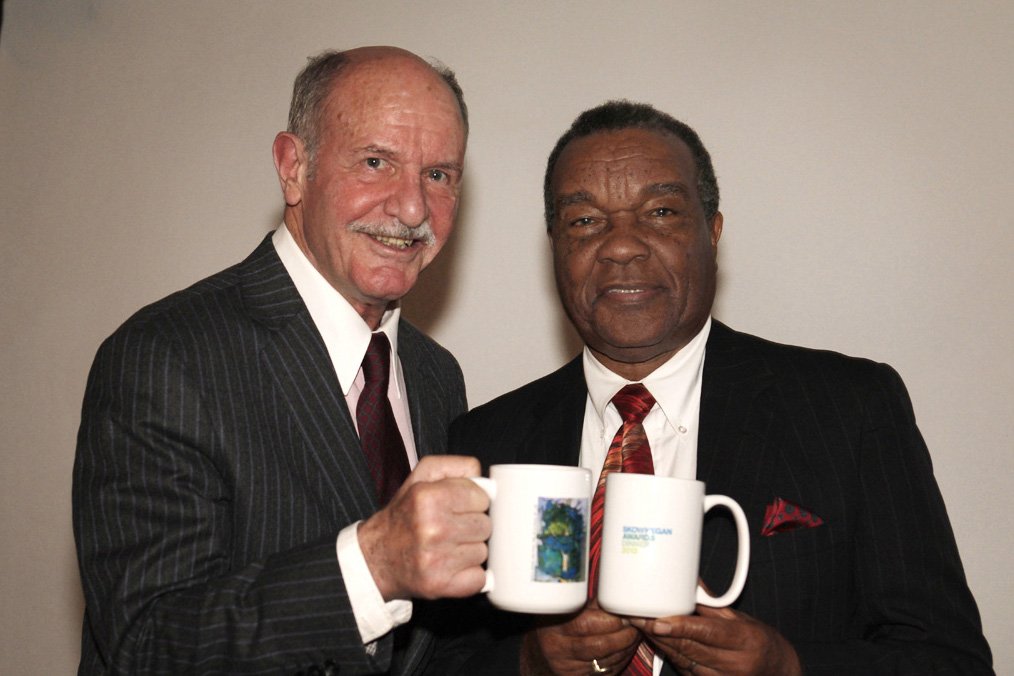

Skowhegan Lifetime Legacy Award Recipient, 2016

“The achievements of David C. Driskell are as grand as Mount Everest,” wrote Keith Morrison in the foreword to Julie McGee’s David C. Driskell: Artist and Scholar. Summarizing his life in this moment, in words that seem too small, too mundane is like trying to squeeze Mt. Everest into a snow globe. The thing about Mt. Everest at a distance is that for most of us it exists in the imaginary. And David, in his life and in his practice, is also something of a legend. Until you met him, you could only imagine him. You’d hear stories—you’d see the pictures—but you, yourself, aren't ever close enough to touch.

Like all great legends, David forever changed the lives of so many. The common ground between his work as an artist, teacher and art historian was his ability to propose an alternative to our understood realities. He was a dissector and a re-builder, who trained his keen eye on the nature of humans, the environment, on political bodies. His approach recalls the ethos articulated by Senagalese poet, politician, and cultural theorist, Leopold Senghor’s who addressed the nature of making art in African cultures at the “Conference of Negro-African Writers and Artists” in 1956. In the essay Princes and Powers, James Baldwin recounts his words: “African art is concerned with reaching beyond and beneath nature, to contact, and itself become a part of la force vitale. The artistic image is not intended to represent the thing itself, but, rather, the reality of the force the thing contains.”

This artistic image that Senghor proposes, in David’s art practice, began with vision, then the deconstruction of vision, and then a reconstruction of that vision. He sought not to portray the reality of any given object or event, but instead to infuse it through collage, through line, through color, with an alternate read of its true nature. Each work was imbued with a spiritual exploration that in his own words “vacillate[d] between the ideal order and that which is experienced within the senses.” His interpretation was inherently informed by his personal experience of the world, and yet it transcended the limits of an individual and represented the culture around him.

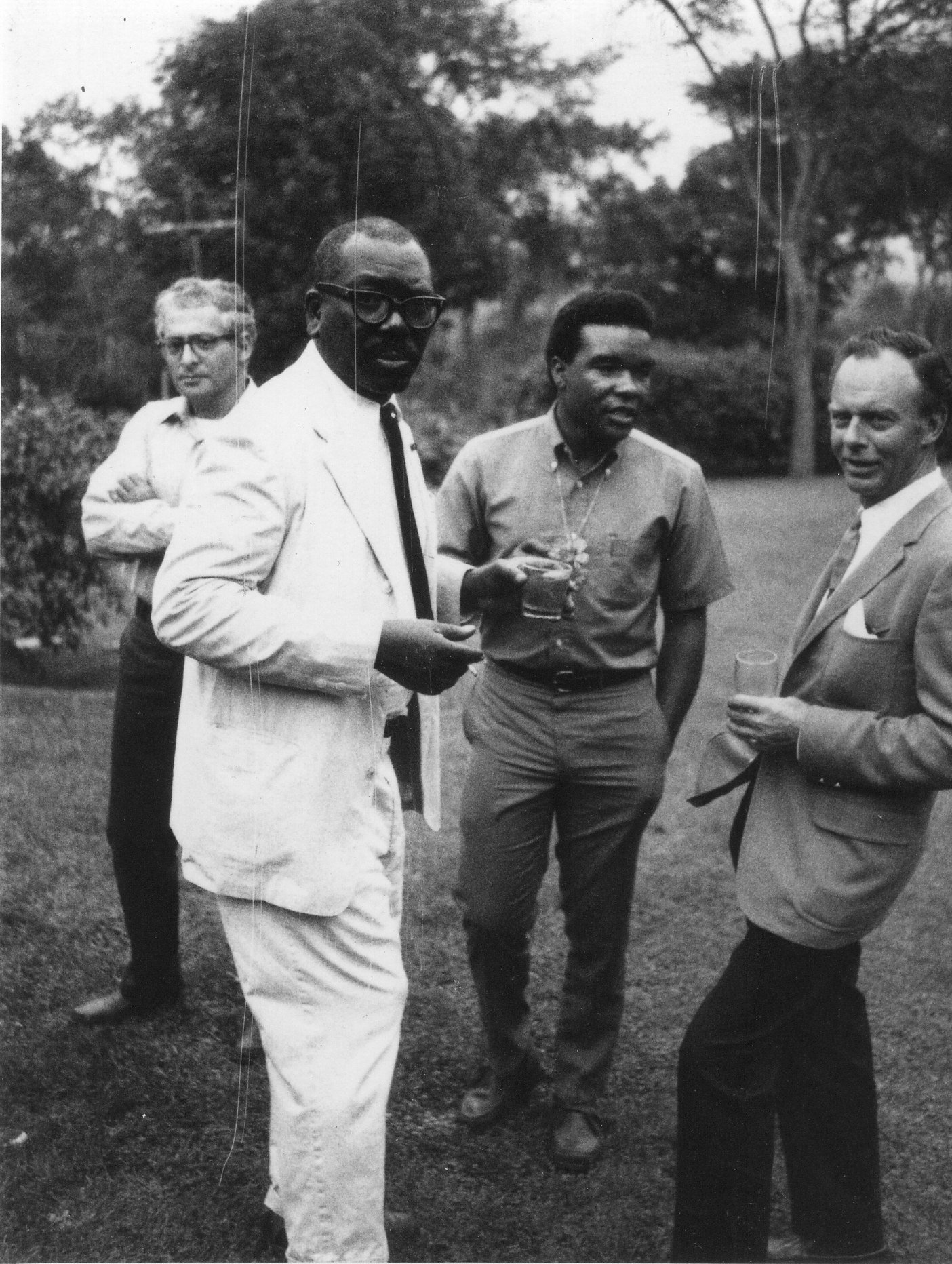

David studied art at Howard University, and received his MFA from The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. He attended the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture and went on to teach at Talladega College, Fisk University and, ultimately, at the University of Maryland, College Park where he held the title of Distinguished University Professor of Art, Emeritus. It was also where The David C. Driskell Center for the Study of Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora is named in his honor. Over his long and prolific career, David received thirteen honorary Doctorates.

His own work had been included in over 26 solo exhibitions and group exhibitions from around the world: Port Elizabeth, South Africa; Santiago, Chile; and New York—all of which will be the subject of a forthcoming career retrospective which will travel to the Portland Museum of Art in Maine, the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, after its 2021 launch at the High Museum in Atlanta, where they established the David C. Driskell Prize in 2005. It was the first national award to honor and celebrate contributions to the field of African American art and art history. In his life, David authored five books on the subject of African American art, and co-authored four others. In 1976, David curated the groundbreaking exhibition “Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950,” which has been a foundation for the field of African American Art History. In 2000, he received the National Humanities Medal, awarded to him by President Bill Clinton, and in 2016, Skowhegan proudly awarded David with its first ever Lifetime Legacy Award for his contributions to Skowhegan and the world in which Skowhegan exists.

David’s artistic accomplishments are as impressive as any one artist could want, but his proposition of an alternate to a reality that we think we know is not simply an act of individual visual expression—it is a transgression that David pushed beyond the picture plane, into curatorial, art historical, and teaching practices that have literally changed how we understand, look at, and even recognize the work of black artists.

Recognized as a founder of African American Art History, David’s curatorial and art historical work was not about creating a category for African American Art, instead he, himself, has claimed a space for art produced by Black Artists to be discussed, revered, viewed with the same level of importance and impact as art produced by others. David has said: “I make art to free myself, to give a new dimension to life, and hopefully to other peoples’ lives through this personal act of freedom I put on canvas.” He has done the same through his curatorial, writing, and research practices—and in doing so, he has opened a public dialogue that has allowed other artists the freedom to do the same. Many of the conversations we have in the art world today come from his work. Skowhegan’s world, and the art world have been forever changed, made richer, made more radical, made boundary-breaking through his stewardship and care.

This is a difficult time, but David’s passing is a reminder of what to do in difficult times. He often told a story about his parents, despite the social restrictions put on his body, his mobility, his development as black man in the Jim Crow South, encouraging his continued education “if [he] wanted something different than this.”

You work, you care, you change circumstances in spite of the world around you. You alter history, you create new histories, and in turn, new futures. And even with all of the distance that is part of this specific moment, this specific unforeseeable pandemic, we find ways to do that work, whether seen or unseen, in danger and in safety. You do it before the world is ready for it, before it can even really see or accept the changes you have made. David did it with grace and humility, and because, in his own words, “someone has to do it.” So many of us have space for our voices because of his work and we don’t even know it.

But David didn’t seek glory—he was glory.

David C. Driskell Acceptance Speech

Lifetime Legacy Award

Skowhegan Awards Dinner

April 26, 2016

The Plaza, New York City

Presented by Mark H.C. Bessire, Director of the Portland Museum of Art

The Pivot

Featuring the class, faculty and staff of 2015.

Interview with artist Suzanne McClelland (F '99) and excerpts from the Skowhegan Oral History Project interviews conducted by Liza Zapol with artists David C. Driskell (A '53, F '76, '78, '91,'04) and Bill King (A '48, '51, '52, F '67, '76, '77, '82, '89).

Created for Skowhegan by RAVA Films and Wesley Miller (A '02).

Made possible by Trustee Jan Aronson.

To learn more about The David C. Driskell Center, please click here.

Images courtesy of Skowhegan Archives, David C. Driskell Center, Liza Zapol, Christian Grattan, BFA, and Patrick McMullan.